Image: Andreas Pöschek

Image: Andreas Pöschek

Gasometers occupy a unique place in the urban and cultural landscape. In cities around the world, these circular structures loom large, imposing remnants of a fast-fading — perhaps already past — industrial age. In many places, they lie deflated or disused, emptied of the gas they once housed — a skeletal frame the only trace of the figure they once cut. In Vienna, however, things are different.

Image: Andreas Pöschek

Image: Andreas Pöschek

Built as part of the city’s gasworks in the dying years of the 19th century, then used until 1984 after the switch from town gas to natural gas, which saw them shut down and forsaken, four of these former gas containers still stand tall today. Here in the Austrian capital, these behemoths of a bygone era present not a sorry profile, but rise up in all their past glory — repurposed for contemporary times.

Gasometer C. Image: Andreas Pöschek

Gasometer C. Image: Andreas Pöschek

Saved from the wrecking ball by their status as historical landmarks — their red-brick exterior walls preserved — Vienna’s restored gasometers are clearly recognizable as what they once were. Multi-level zones for living (top floors), working (middle floors) and entertainment and shopping (ground) are found within the cylindrical structures that once housed the city’s gas supply.

Image: Dezidor

Image: Dezidor

Once, these massive round buildings were used as storage tanks for the gas that was dry distilled from coal before being distributed into the city gas network — first for street lamps, then, by 1910, for cooking and heating in homes. Now they serve as spaces for apartments, offices and malls — the latter connected to the upper levels by skybridges; a sign of the shift from the consumption of fossil fuels to the consumption of commodities, although not all the commercial areas are used.

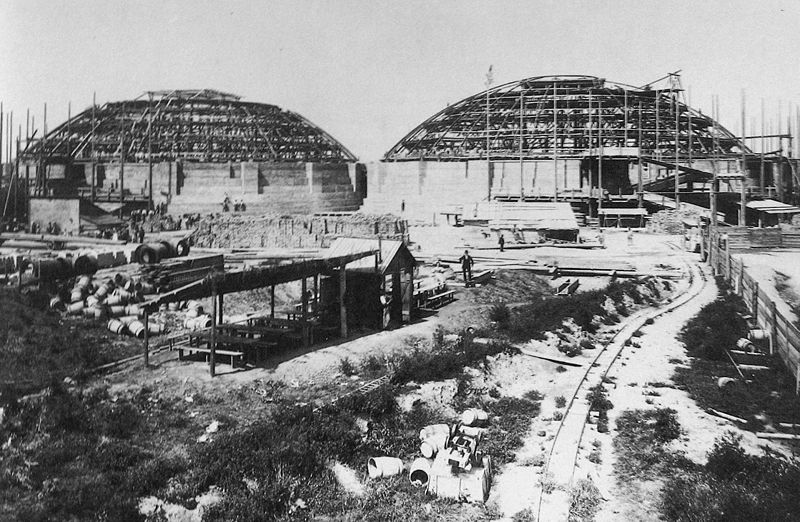

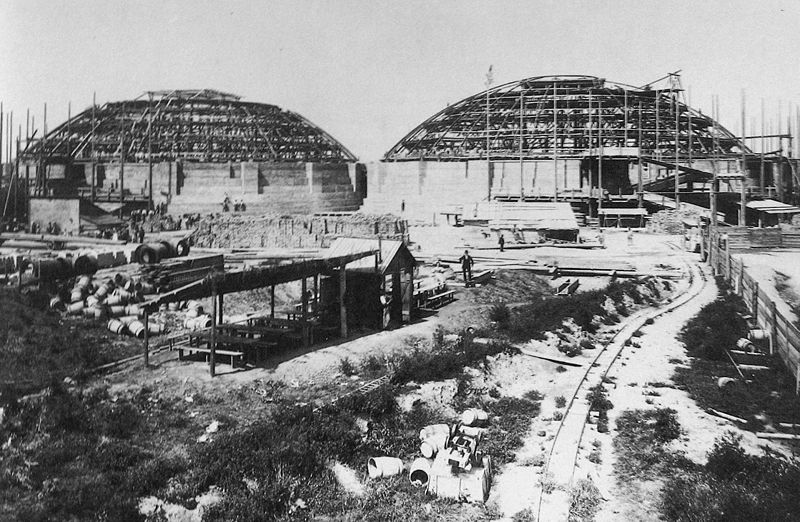

Image: Vienna Museum

Image: Vienna Museum

When they were completed in 1899, Vienna’s telescopic gasometers were the largest in all of Europe, each with a volume of some 90,000 m³, seated in a water basin and enclosed by a brickwork façade. Their scale is still impressive in the cityscape, each one towering 70 meters tall and measuring 60 meters across.

Image: Der Falk Von Freyburg

Image: Der Falk Von Freyburg

There are interesting parallels between the turn-of-the-century birth and rebirth of Vienna’s gasworks. Both were the result of design contests: In 1892, Schimming, an engineer from Berlin, won the pitch to build the structures; while in 1995, another architectural competition was launched calling for ideas in favor of new uses for the grand yet retired and abandoned structures.

Gasometer B. Image: Danny Hennesy

Gasometer B. Image: Danny Hennesy

By 2001, four architects had seen their ideas realized for their different interpretations of the gasometers, from Jean Nouvel’s translucent roof, which plays with reflections, refractions and transparencies of the old and the new (Gasometer A), to Manfred Wehdorn’s indoor garden and eco-friendly-designed terraced structure (Gasometer C). The old had been instilled with a new lease of life.

Gasometer B. Image: Pudpuduk

Gasometer B. Image: Pudpuduk

During the process of remodeling and revitalizing these relics of industrial society, the gasometers were completely gutted, so only the brick exterior and parts of the roof were left fully intact. Yet the reuse of the existing buildings’ encircling façades was nevertheless something of a design coup. With total demolition sidestepped, the resulting waste generated by razing the gasometers to the ground was minimized — while these icons of industrial architecture looked on.

Gasometer B. Image: Andreas Poeschek

While the grunt of physical labor set to the tune of clanging machines can no longer be heard in Vienna’s Gasometer City, these days the solidarity of working men has given way to a different sense of identity. A village feel is said to prevail in this city within a city, a spirit of community evident both among the 1,500 people who live here and online at the Gasometer Community.

Gasometer D. Image: Andreas Poeschek

Gasometer D. Image: Andreas Poeschek

In neither their past nor present incarnations have these gas containers been empty vessels. They have been brimful of energy — or at least its potential. And, the structures, which were featured as a location in James Bond movie

The Living Daylights, are set to die another day.

Sources: 1, 2, 3

Image: Andreas Pöschek

Image: Andreas Pöschek Image: Andreas Pöschek

Image: Andreas Pöschek Gasometer C. Image: Andreas Pöschek

Gasometer C. Image: Andreas Pöschek Image: Dezidor

Image: Dezidor Image: Vienna Museum

Image: Vienna Museum Image: Der Falk Von Freyburg

Image: Der Falk Von Freyburg Gasometer B. Image: Danny Hennesy

Gasometer B. Image: Danny Hennesy Gasometer B. Image: Pudpuduk

Gasometer B. Image: Pudpuduk

Gasometer D. Image: Andreas Poeschek

Gasometer D. Image: Andreas Poeschek