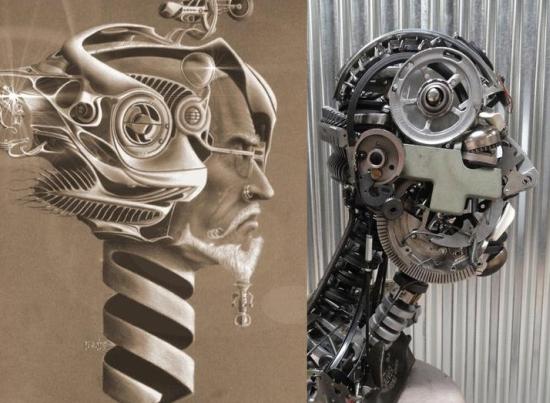

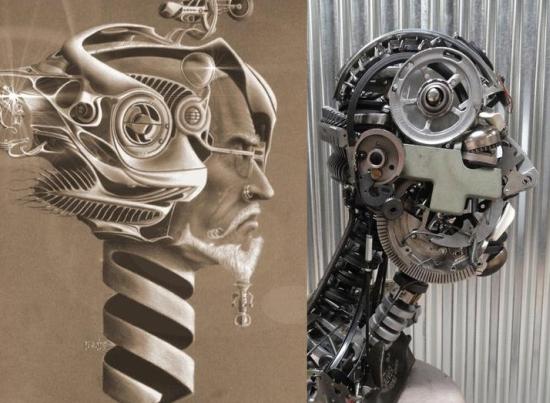

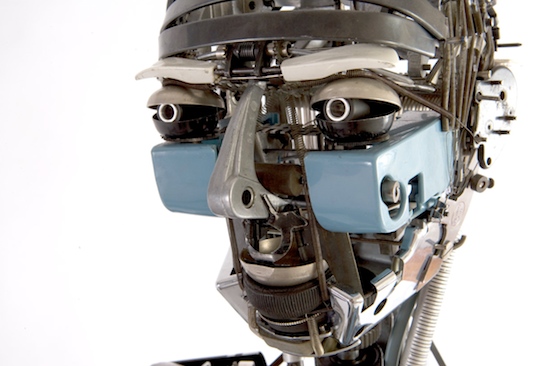

“Bust V (Grandfather)”

All images courtesy of Jeremy Mayer and used with permission.

With the advent of the personal computer, typewriters became obsolete fast. Even the most loyal typewriter user have probably by now switched to a computer. Still, though hardly used, typewriters are still around, even if they’re only gathering dust in attics, basements and offices.

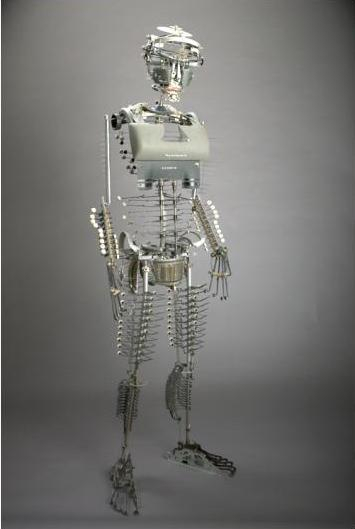

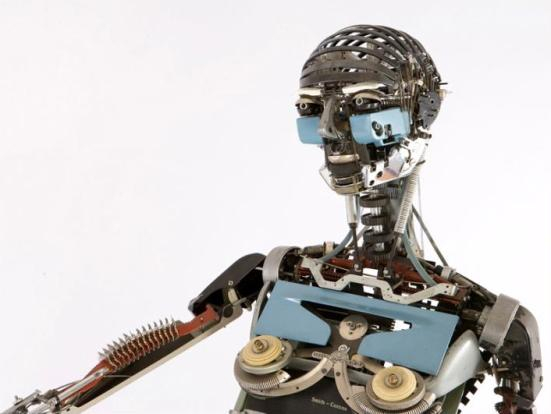

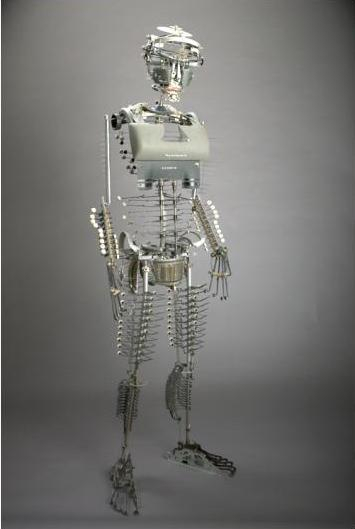

“Nude IV,” (Delilah, 2009)

So, what to do with the millions of old machines? Oakland, CA-based artist Jeremy Mayer has found a solution: He turns them into incredible sculptures.

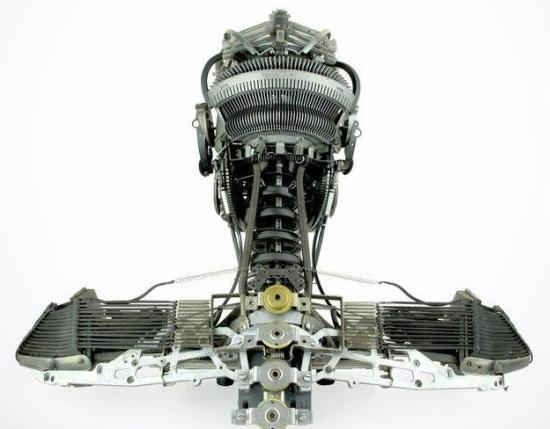

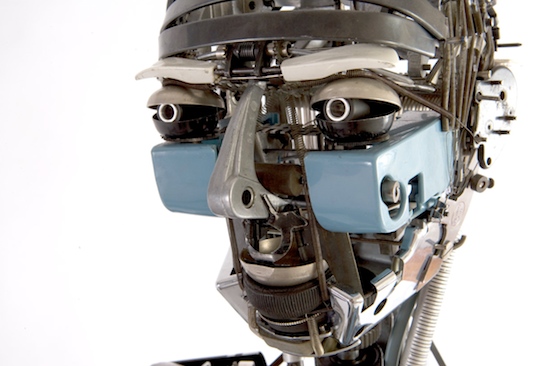

“Bust III” close-up

Looking at the human body and a typewriter alongside each other, we wouldn’t necessarily think that one resembles the other. This is where Mayer’s talent comes in. If you didn’t believe that typewriter faces can look scary, sexy or wise, take a close look at his work. After disassembling one or more typewriters, he takes those parts that resemble elements of the human anatomy and reassembles them to build busts, bodies or whole typewriter people with astonishing results.

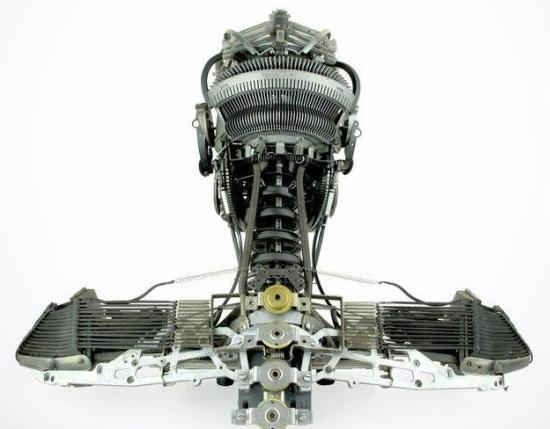

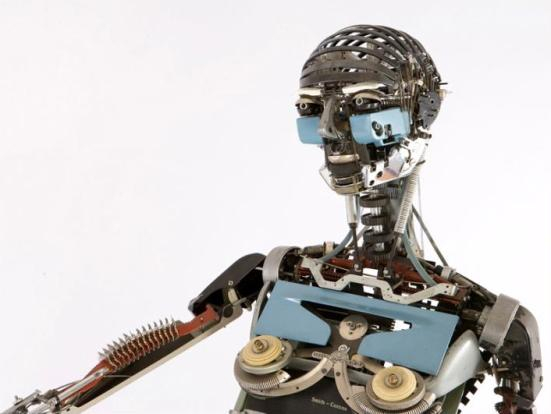

“Bust IV”

As we browse through Mayer’s work, you will notice that there are few (if any!) typewriter parts that do not resemble a feature of the human body. A mechanical part becomes a human spine; a typebar a finger. Surprised? We sure were.

“Bust II,” (2004)

And the recycling aspect is just divine, literally. Mayer believes that everything in this world, natural or human made, is part of one closed system. Not everything can be recycled, though, so we need to be creative and, in his words, “Take everything we have, pick it all apart, choose the best parts and reassemble it.” A modern recycling mantra.

“Bust V” (Grandfather)

As if the sculptures themselves weren’t incredible enough, Mayer’s technique definitely is: it’s assembly in its purest sense — he uses no binding agents or tools. He specifies: “I do not solder, weld or glue these assemblages together; the process is entirely cold assembly.” This means that all parts are also movable. Plus, he does not add any pieces that have not come from a typewriter.

“Nude IV,” (Delilah, 2009)

Yet this doesn’t make for any restrictions in terms of expression. “There are some very sexy parts of human anatomy that draw you to the machine,” says Mayer. And looking at a sculpture like “Nude IV (Delilah)” above, we have to agree. A piece of this size usually takes Mayer about a year to assemble — it is made from close to 50 typewriters — and sells for around $20,000.

Delilah was modeled on Mayer’s girlfriend of the same name. Her breastplate was made from the top ribbon cover of a Royal Safari and the breasts come courtesy of the gears for the ribbon advance from a Remington.

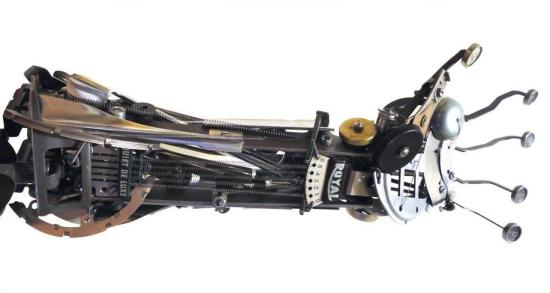

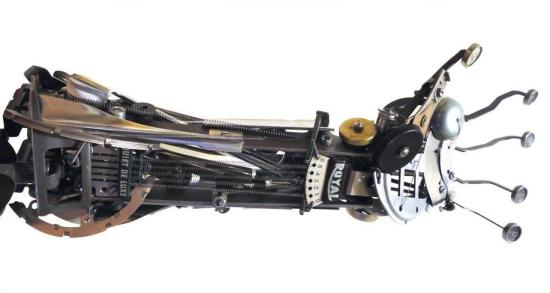

“Hand I,” (2009)

Being a purist has its limitations too, as it prevents Mayer from making his sculptures move. This would require electronics and programming, and thus mean adding non-typewriter parts. He does, however, usually add one small element per sculpture that is kinetic in the broadest sense, such as eyes that move or bells that ring. But they’ll never become the focus of a piece and are often just known to Mayer and the final owner of the artwork.

“Nude II,” (2000-2001), here at the Nevada Museum of Art, November 2007

Apart from the disassembly and reassembly, a big chunk of the full-time artist’s work is spent on categorizing and sorting each piece. Sketching every new project on the computer and using a real-life model are also important preparations. A working knowledge of human anatomy is a must, and two well-thumbed anatomy books have been Mayer’s trusty companions throughout. (If you want to know how anatomically correct his sculptures are, just look at the “Nudes” closely.)

Reassembly is a tough and time-consuming exercise. Mayer explains: “The reassembly is very time intensive. For example, to do an arm, I have to figure out first what parts I want to use for the larger pieces that correspond to the humerus, the ulna, radius, digits, deltoid muscle, bicep, etc. Then I have to figure out how to connect them to each other by recognizing existing holes and connections on the pieces and utilizing the myriad of other smaller parts (screws, pins, set-pin collars, springs, plates, flanges and such) to fit into those holes and connections.” Sounds like one big puzzle to us.

“Hand III” (2010)

For Mayer, a typewriter holds a myriad of possibilities — not only as a mechanical object, but also as a microcosmos. He explained his fascination in an interview with

Make magazine: “I had, from a pretty young age, wanted to take a typewriter apart or live inside of one. I used to stare at my mom’s Underwood and imagine myself inside it as a city, like in Fritz Lang’s

Metropolis.”

“Nude II,” (2000-2001)

That’s quite an imagination, but after reading this article and seeing more of Mayer’s work, you’ll see that it’s not so far-fetched either.

“Nude III,” (Olympia, 2007)

Surprisingly, it took Mayer a while until he got a chance to delve into the inner workings of his first typewriter. He recalls, “When I finally got a hold of one that was a ‘stray,’ so to speak, I very gleefully took it apart. This was in my early 20s, and at the time I had been playing around with drawings that depicted flying heads with a sort of tech-mashup, neo-Baroque thing going on. The components of the typewriter fit right in line with that aesthetic.”

Looking at this early drawing, we can see Mayer’s mind working in a kinetic direction, and he admits, “My mind keeps coming back to this drawing I did exactly 20 years ago when I was 19. I put my latest sculpture next to it and it’s easy to see why. I feel like I’m finally getting to the point that I can do things with typewriter parts that I’ve always wanted to do with traditional sculpture methods.” Brace yourself for more awesomeness!

“Nude,” (1995)

As symmetry is key for Mayer, finding the right parts is not easy. In fact, one of the challenges of Mayer’s art is finding various typewriters of the same brand and model to guarantee this symmetry. He often needs four or even six machines for one sculpture; more for a life-size one.

“Bust V” (during reassembly)

It helps that Mayer is now quite well known and so often gets donations from fans and friends. Otherwise, it’s flea markets, thrift stores and Internet swap and recycling sites that he turns to to support his art. His favorite typewriter model is the Royal Safari because of its sensual look. It’s hard to find, though, so he usually uses Smith Coronas, Underwoods and other Royal models.

“Nude III,” (Olympia, 2007)

For critics out there who feel bad that he takes apart good typewriters, rest assured that Mayer focuses on easy-to-find machines that are neither in good condition nor worth repairing. And should he come across a vintage rarity, like, let’s say an Olivetti Valentine, he’d be the first to know its value and send it to a museum.

“Torso,” (2003)

As far as encouragement is concerned, Mayer got his first understanding glances from the typewriter repairmen he hounded for spare parts back when working in Iowa: “A lot of them understood because all these years they had been looking at these pieces and going, ‘Hmm, this looks like a dude… a dude walking his dog!’”

“Torso,” (2003) close-up

He continues, “Sometimes they would have little figures they had made over their bench, or some hint that they understood these pieces to be either anthropomorphic in and of themselves, or a component of some living thing.” That was enough to know he was onto something and continue experimenting despite the often puzzled looks of those immediately around him.

In the studio…

Being surrounded by so many letters all the time does offer Mayer the temptation of forming words, clever puns, maybe, but so far he has resisted spelling anything in a bid to remove his creations from the context of writing machines. He says of his work: “I like to think of it as a post-apocalyptic exercise. After the apocalypse, there’s this guy in the junkyard making stuff for the village.” We like this image a lot. Mayer adds, “The brain is the typewriter of the future.”

“This is how they all start out — with a spine and a pelvis.”

Mayer is a member of the multifaceted group of artists called Applied Kinetic Arts (A.K.A.), one of whose members,

Nemo Gould (and his mechanical sculptures), we have featured here on 1-800-RECYCLING.com before. Mayer gets his inspiration from science fiction, industrial design, anatomy, architecture and classical figurative sculpture, among many other sources.

“Nude II” and “Nude III” on display at the Nevada Museum of Art, November 2007

Though he studied engineering and material science at the University of Nevada – Reno for a year, Mayer never took any formal art classes. His talent has shown through from an early age, though, and he has been selling his paintings and drawings in galleries since the age of 14. His typewriter sculptures have been exhibited in solo and group shows throughout the U.S. Make sure to check out his

website for his amazing typewriter animals and other projects.

“Mask III,” (2003)

If you have an old typewriter lying around at home, you could donate it to a museum or give it away for recycling. Typewriters are made out of cast iron, aluminum, stainless steel, hardened steel and copper — many different, valuable metals that can be reused or recycled.

Additional sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Delilah was modeled on Mayer’s girlfriend of the same name. Her breastplate was made from the top ribbon cover of a Royal Safari and the breasts come courtesy of the gears for the ribbon advance from a Remington.

Delilah was modeled on Mayer’s girlfriend of the same name. Her breastplate was made from the top ribbon cover of a Royal Safari and the breasts come courtesy of the gears for the ribbon advance from a Remington.

Reassembly is a tough and time-consuming exercise. Mayer explains: “The reassembly is very time intensive. For example, to do an arm, I have to figure out first what parts I want to use for the larger pieces that correspond to the humerus, the ulna, radius, digits, deltoid muscle, bicep, etc. Then I have to figure out how to connect them to each other by recognizing existing holes and connections on the pieces and utilizing the myriad of other smaller parts (screws, pins, set-pin collars, springs, plates, flanges and such) to fit into those holes and connections.” Sounds like one big puzzle to us.

Reassembly is a tough and time-consuming exercise. Mayer explains: “The reassembly is very time intensive. For example, to do an arm, I have to figure out first what parts I want to use for the larger pieces that correspond to the humerus, the ulna, radius, digits, deltoid muscle, bicep, etc. Then I have to figure out how to connect them to each other by recognizing existing holes and connections on the pieces and utilizing the myriad of other smaller parts (screws, pins, set-pin collars, springs, plates, flanges and such) to fit into those holes and connections.” Sounds like one big puzzle to us.