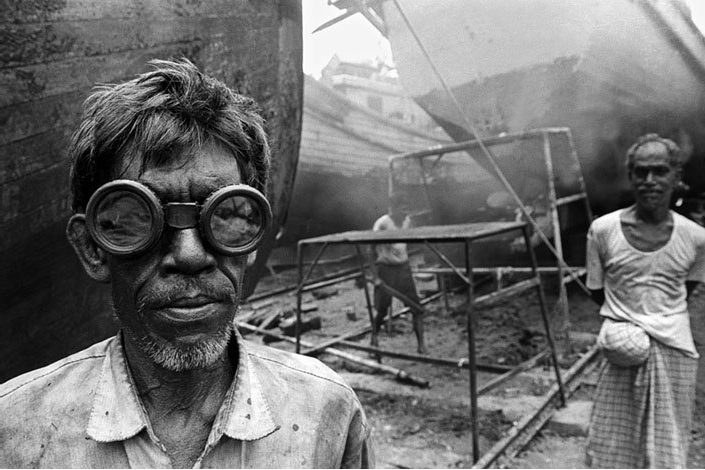

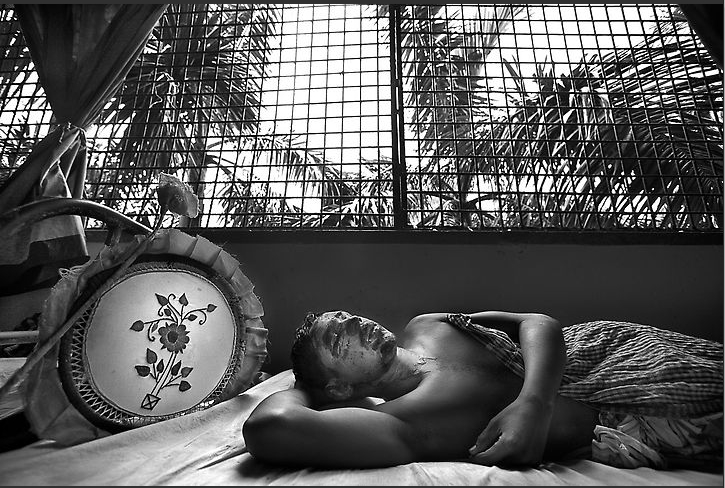

Spread along the shore of the Bay of Bengal, just a few miles north of Bangladesh’s second city, lies a stretch of beach home to a hellish recycling site like no other on earth. Welcome to the ship breaking yards of Chittagong.