d-CON Mary (detail), 2008. All images used with permission of Jason Clay Lewis.

It’s often said that you’re never more than 8 feet from a rat in London, and in the even more densely populated urban sprawl of New York, lordy those scuttling vermin must be within touching distance — and you may not even know it. Perhaps it was thoughts like these that first drove Jason Clay Lewis to reach for the rat poison. But then somewhere along the line, the Big Apple-based artist decided on an alternative use for this deadly means of pest control — repurposing both the poison and its packaging as the very materials from which to create his next sculptural works: portrayals of religious icons, at once beautiful and strangely repellent. Among the diverse pieces of art that make up Lewis’ Renewal Series are various iconographic reproductions covered with d-CON rat poison packaging. Towering above the others, both in scale and in notoriety, is a 5-foot-tall sculpture of the Virgin Mary — the lurid yellow of the layered poison packs that form the skin of this life-size Madonna a stark reminder of art’s capacity to shock and unnerve, particularly in a still strongly Christian country like America.

d-CON Mary

As with any artist, the medium within which Lewis works is fundamental to the meaning of his pieces and some of the aesthetic ideas with which he is playing, such as the relationship between pleasure and disgust. However, we were also curious as to how he first discovered and settled upon these specific materials, and how the concept of recycling — or at least reuse or repurposing — figures in his work. Lewis told 1-800-RECYCLING: “I am a very tactile person, so I am drawn to materials that are slightly odd or have the potential for having double meanings. It has been a long transition, as I have used so many different materials. I try to push my work, so the poison pieces came about because it just seemed like the craziest thing to use for a sculpture. By using the d-CON boxes — with their prominently displayed bar codes — I believe it pushes the idea of what religious symbols can be, and questions not only the innocuousness of religion, but also the commercialization of religious iconography.”

Poison Christ, 2008

The phantom of the afterlife and instruments of death pervade Lewis’ body of work in a variety of forms (“The Black Death,” engraved bullets). What’s more, he does not stop at using the packaging of poison, just as he does not restrict himself to the representation of Christian religious icons. His statues of Christ and Buddha are composed of rat poison itself — the former, part of the “Drop Dead Gorgeous” series that spawned d-CON Mary, standing over 6 feet tall. What are we to make of the use of “found substances” that would normally spell death for vermin having artistic life breathed into them by Lewis’ hands and mind? It certainly makes us ponder when that which would exterminate the lowliest of animals assumes an exalted status in the image of our most revered and recognizable religious forms. The statement accompanying a recent exhibition explained: “The poison pieces reference empathy: As we go up the food chain, our empathy increases until we reach the ultimate form represented by the crucifixion. Lewis’ fascination with religious topoi — seen throughout his work — this time focuses on semiotic ambivalence of Christian iconography.”

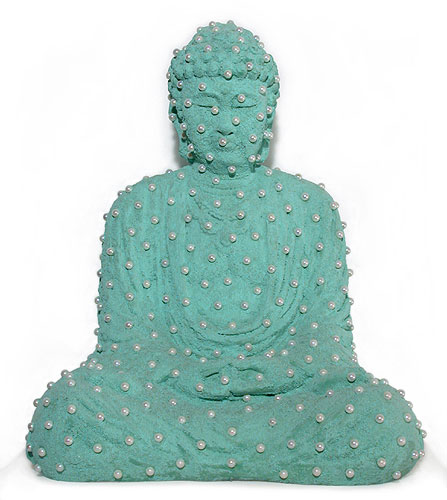

Poison Buddha

But, as mentioned, the icons of other world religions are not exempt from Lewis’ critical gaze. Buddha puts in an appearance at the party — the enlightened one also awakened in the blue-green hues of rat poison. Shedding some light on this uneasy balance between repurposed form and recycled content, Lewis told 1-800-RECYCLING: “My work is at its most powerful when I place extreme opposites together, such as good and bad or positive and negative. This is highlighted most profoundly when I use my favorite topic of life out of death and the cycle of life. By juxtaposing the spiritual iconography with poison, I hope it brings about in the strongest way possible the idea of the fragility of life and how religious icons are used as representations of the afterlife.”

Poison Easter Bunny

Lewis’ challenges to the perceived order of things — questioning concepts such as beauty, passion, life, death and creation — do not always have such a sober incarnation. His Poison Easter Bunny references a character that is only part of Christian folklore in its broadest sense. Yet even beneath the toxic surface of this more playful and not strictly religious icon, there lurks a serious intent from an artist for whom art is: “A matter of life and death, where one senses the only response to death is art. Without glossing over the violence of the natural world I ask questions about man’s suicidal folly, the one we call progress, a merger into a religion of commerce and profit, of false façades… ” Through his unique choice of media, his reuse of dark and sometimes dangerous materials, Lewis is an artist who seeks to go beyond the limits imposed by culture and tradition, all the while exploring his ideas of “attraction verses repulsion.” Could the scratching of rats be music to your ears? Doesn’t poison and d-CON packaging almost look good enough to eat? Special thanks to Jason Clay Lewis for answering our questions and for permission to use the images from his website.