“Woman With Connections,” 2005, electronic connections. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

Federico Uribe’s torso pieces might all come in roughly the same shape, but consisting of a vast array of recycled everyday items, they couldn’t be more different.

“La Femme Fatale,” 2000, baby bottle nipples. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

Reusing the commonplace is fundamental to Uribe’s artwork. Items are stripped of their practical purpose by being reassembled into new shapes, leaving only the color, form and texture of the original objects. By recycling seemingly boring shapes, Uribe hopes to reawaken an appreciation of their beauty as if they were being seen for the first time.

“Dominatrix,” 2004, dominoes. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

While having a distinctly modern flavor, suggesting pop art’s reappropriation of the everyday, Uribe’s torso pieces also recall the marble forms and contours of classical art — as if Roman sculpture had been reworked in cans of Campbell’s soup.

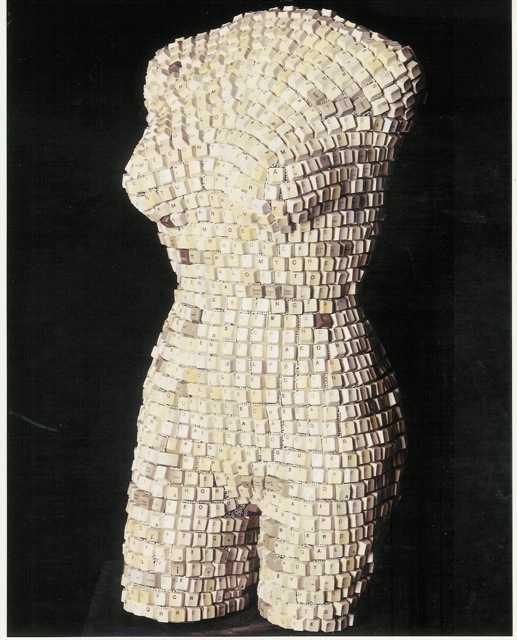

“Cybersex,” computer keys. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

In fact, Uribe’s pieces are made from all manner of materials, from dominoes, screws and computer keys, to plastic forks, brushes and cleaning supplies, as well as a host of other found objects. The only requirement is that they must inspire the artist’s “aesthetic instinct” of beauty.

“La Bocalista,” 2000, rubber lips. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

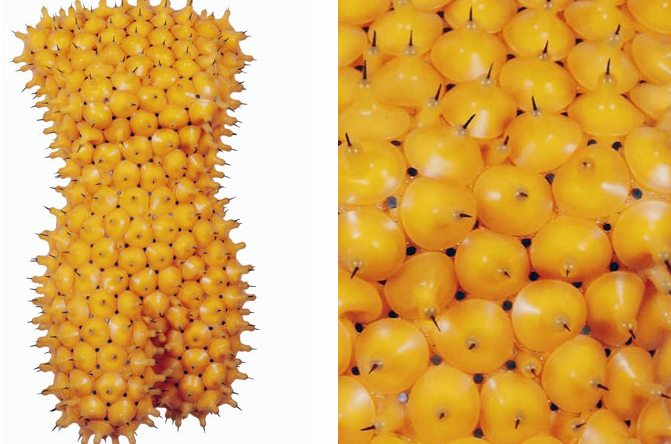

The creation of the sculptures is a labor-intensive process, requiring compulsive repetition as the disparate elements are weaved together to form a whole. In the piece above, rubber lips have been brought together into the human form — with the lips meeting as flowers. Meanwhile, below is “Still Life,” which sees plastic fruits stitched together in a subversion of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s well-known paintings of vegetables, piled into human figures.

“Still Life,” 2000, plastic fruits. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

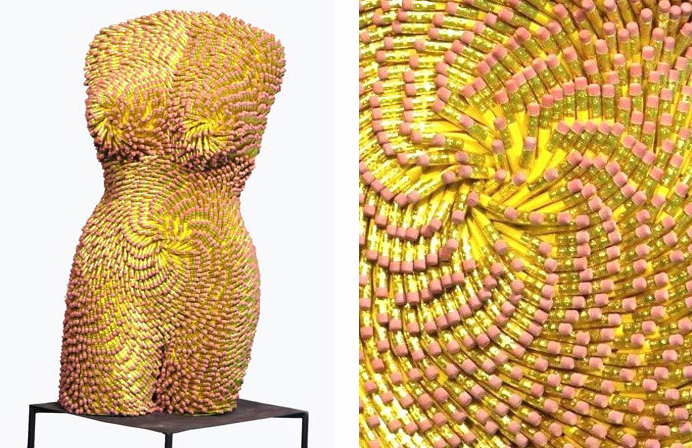

Several pieces use similar objects to very different effects — for example “Bleeding Bride,” below, uses pencil heads to form a spiky, cactus-like form from color pencils, while La Fautive uses pencil erasers to form a smooth, calmer form.

“Bleeding Bride,” 2005, pencil heads. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

“La Fautive,” 2005, pencil ends. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

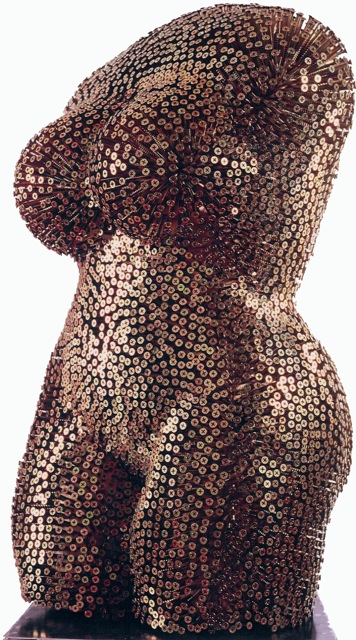

Disarmingly, the pieces have been given humorous names, using simple wordplay and recycling popular metaphors to affirm their basic positivity. The playful titling explores the way that that the names of the objects fit into the language, while subtly highlighting the extraordinariness and the oddness of the everyday. For example, a series of busts made of screws is called “Everybody gets screwed,” combining a simple pun with the unpleasant notions of having screws driven into oneself and the metaphorical notion of “being screwed.”

“Screwed,” screws. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

In the early part of his career Uribe was concerned with similarly dark themes, working as a painter to explore dark and brooding canvases, preoccupied with Catholic themes of sexuality, pain and guilty.

“Dominatrix,” dominoes. Used with permission of Federico Uribe and Annina Nosei Gallery.

His great turning point came in 1996, in Guadalajara, Mexico, when he began trawling street markets for odds and ends, looking for baby-bottle nipples, screws and plastic forks. With an assembled collection of shapes, it was only a short step to reusing them to assemble sculptures of the human form.

“Secretary,” 2004, computer keys. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

“Mujer Embalada,” 2004 bullets. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

This new period came with a change of heart: his pieces would endeavor to instigate positivity. His ultimate ambition became to inspire a lasting sense of humor, beauty and love in the memory of his audience.

“Candidata,” 2004, padlocks. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

Uribe says, “I have the hope that people who relate to my sculptures and live with them will see the love I put into them. I want people to feel that I do this with a lot of careful attention and the purpose of beauty. I give my life to my work and I want people to see it.”

“Mujer Domestica,” 2005, clothes pegs. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

“Hooker,” 2006, safety pins. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

Uribe is serious when he talks about passion. The sculptures are intended to assume a physical, sensual presence, enticing the viewer to feel their form and texture, stripped of the mundane origins of their components by the radical transformative process.

“Puzzled,” 2003, jigsaw puzzle pieces. Used with permission of Federico Uribe and Annina Nosei Gallery.

Uribe explains: “If a sculpture makes viewers smile or compels them to want to touch it, then, I believe, it becomes a permanent and amiable memory, which generates affection and love.”

“Mujer Centenaria,” 2003, coins. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

“Blonde,” 2005, jute. Used with permission of Federico Uribe.

Federico Uribe’s work can be found at his website, here.