Flower beetle (Cetoniidae) Torynorhinna Flammea, 3 inches. All images courtesy of Mike Libby.

“Move over and let me have a closer look” is something you will often hear from visitors to one of Mike Libby’s exhibitions. Not only because his artworks are — at just a few inches long — fairly small, but also because they so perfectly blend nature and mechanics that one just has to take a closer look to discover their secret.

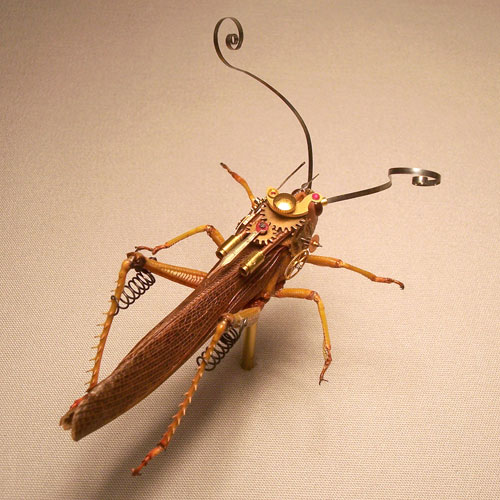

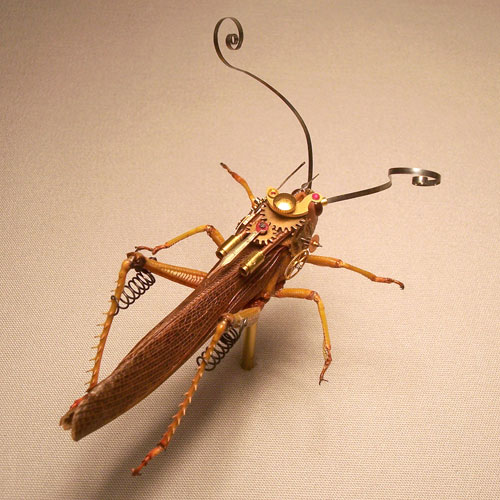

Grasshopper (Orthoptera), 3 inches

Longhorn beetle (Cerambycidae), 4 inches

We’re talking about Mike Libby’s Insect Lab: bees, ants, bugs, grasshoppers and more, which have been cleverly combined with metal and brass gears, springs and clockwork to turn them into mechanical insects. It’s a painstaking process that can take anywhere from 10 to 40 hours per insect.

Dragonfly (Odonata) Anax Junius, 4.5 inches

Ladybug, ¾ inch

Libby questions the common belief that robot-like insects and insect-like robots belong in the realms of science fiction and fantasy. He says:

“In science fiction, insects are frequently featured as robotic critters… In reality, engineers look to insect movement, wing design and other characteristics for inspiration of new technology… Man-made technology is finding that the most maneuverable and efficient design features really [do] come from nature. Ironically and often, this technology closely resembles the musings of science fiction.”

Butterfly (Nymphalidae) Parantica Sita, 4.5 inches

Butterfly (Nymphalidae) Charaxes Tiridates, 4 inches

By putting motors and gears into insects, Libby turns fantasies — ours and those of science — into real-life creations. Isn’t the buzzing of a bee fairly robotic? And aren’t the pathways of a bumblebee automated by the great master that is nature? However one connects with Libby’s creations, they certainly fuel our imagination.

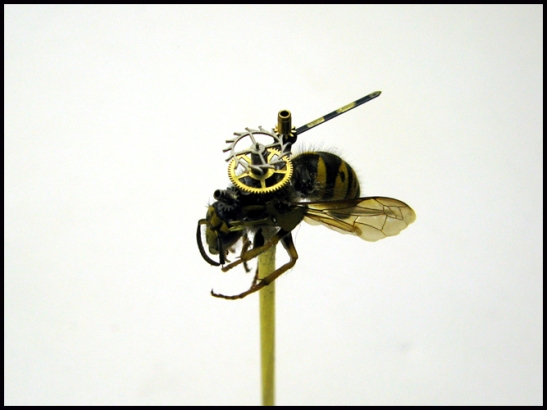

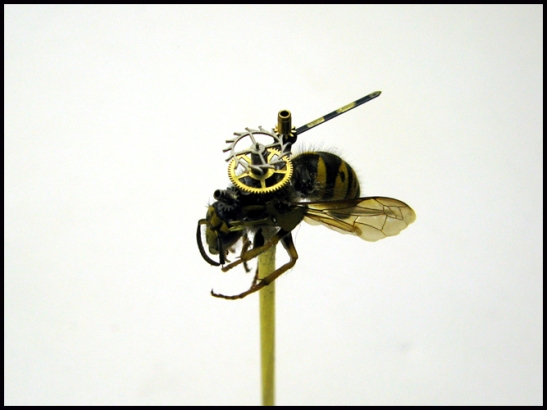

Bumblebee (Hymenoptera) Bombus Pascuorum, 1.5 inches

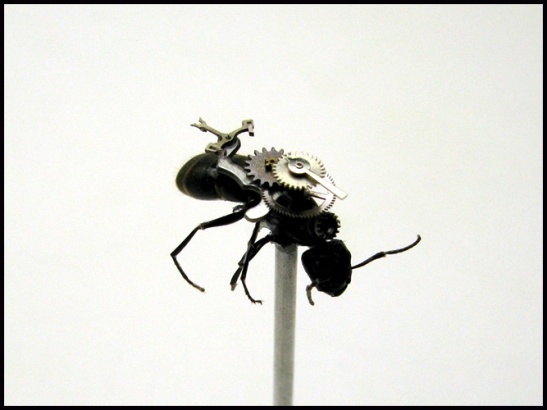

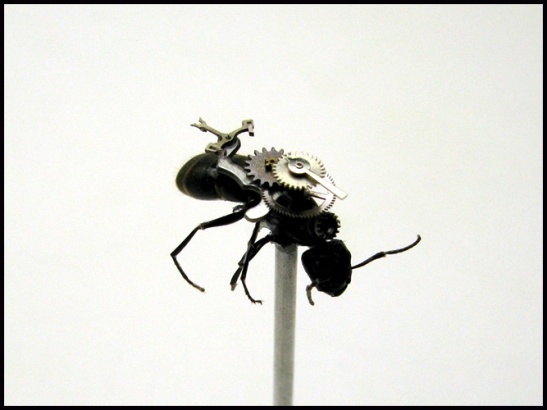

House ant (Hymenoptera) Tapinoma Sessile, ¾ inch

Libby explains:

“This hybridization of insects and technology from both fields [nature and science fiction], is where Insect Lab borrows from. Insect Lab celebrates these correspondences and contradictions. The work does not intend to function, but playfully and slyly insists that it possibly could.”

Praying Mantis

If you think Libby is way off with his creations, think again. Various countries, such as the U.S. and Israel, are already working on robots camouflaged as insects to be used in covert surveillance, for example when fighting terrorism. Robert Wood, leader of Harvard’s robotic-fly project, says, “Nature makes the world’s best fliers.”

Housefly (Arachnidae), ¾ inch

Hornet (Hymenoptera), 2 inches

Because it’s not so easy to recreate nature and come up with a convincingly real robotic bee or bug, another approach is to attach sensors or microchips to actual insects. The U.S. Army has already begun studying the flight patterns of beetles, and from there it’s just a small step to controlling these masters of flight. So, next time you’re stung by a bee or wasp, think again; it might have been a MAV (Micro Air Vehicle).

Wasp (Hymenoptera), 1 inch

Though robotic insects may be the buzz word now, Libby’s fascination started much earlier, namely one fine day about 10 years ago. Libby recalls how it all started: “One day I found a dead intact beetle. I then located an old wristwatch, thinking of how the beetle also operated and looked like a little mechanical device and so decided to combine the two. After some time dissecting the beetle and outfitting it with watch parts and gears, I had a nice little sculpture.”

Longhorn beetle (Cerambycidae) Plusiotis Beyeri, 3.25 inches

The rest is history, and Libby hasn’t looked back since, though apart from creating his clockwork insects, he also makes highly detailed sculptures, models, collages and drawings. But old habits die hard, so Libby can still often be found scouring for dead beetles under vending machines, or in his own back yard, looking for bumblebees, flies, ants, ladybugs and dragonflies. Similarly, no antique pocket watch or wristwatch is safe from his inquiring gaze. And sewing machines and typewriters may also contribute the odd part for his clockwork insects.

Crab, 5 inches

One of his latest pieces was a commissioned project for a longtime patron. Libby says: “[This crab is] a full 5 inches across, found dead at a local shoreline here in South Portland, ME. Customized mostly with brass watch parts and some larger clock parts. I’m pleased with how he came out and am excited to do more of these in the future.” We sure hope so. Here’s a close-up.

Since establishing his website in 2005, Libby’s mechanical bugs have been flying out of the door, and prices have gone up steadily from $200 to $400 to $500 and more than $1,000 a piece. His mechanical insects have been on display in various national and international exhibitions and have been featured in various books — all of which, together with more cool creations, can be found on his

website.

We’re sure we can expect more exciting stuff in the future, and if we won’t see Libby’s creations in the next Bond film, who knows, maybe he’ll be approached by secret service agencies from around the globe soon. We’ll keep following the buzz.

Special thanks to Mike Libby for readily providing images and information for this article.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5