All images used by permission of Helen Altman.

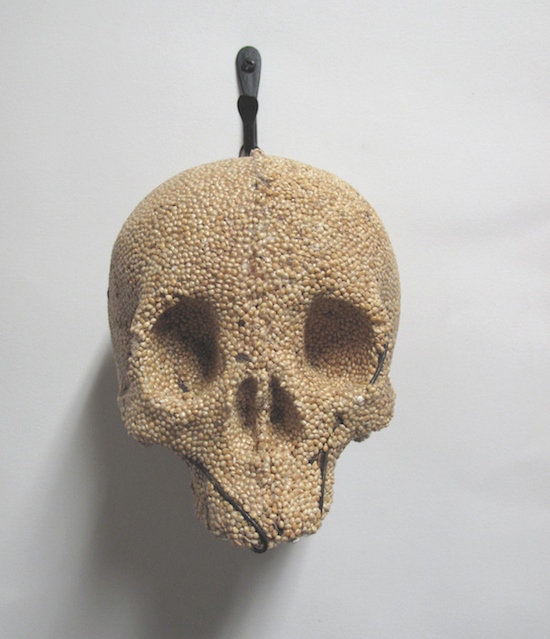

Hollow eye sockets look deadpan, except to those who might construe an expression. The crack in the cranium leads down to an upper jaw whose dental history will never be known. The empty cavity a nose would have once covered is conspicuous in its fragility — and in what it reminds the observer is different about the skulls on display: their aroma. The scent hanging in the air is less cadaverous than culinary, more kitchen than corpse. The space these many-hued death’s heads inhabit is redolent with the smell of spices, which they are in fact made of. Each skull’s texture reveals its true nature — be it aniseed, balsam fir or bamboo; calendula, yellow mustard or fennel seed.

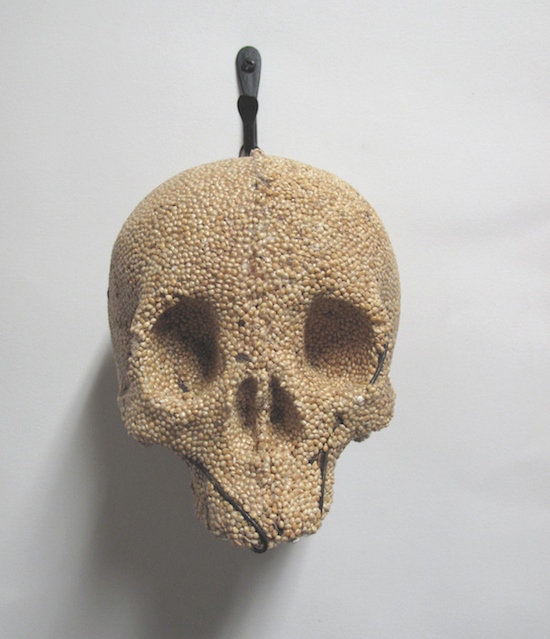

Millet Seed Skull

These are Helen Altman’s Spice Skulls, almost lifelike skeletal human heads, meticulously crafted in the motley colors of the foodstuffs the Texas-based artist has chosen as her medium. Altman molded each macabre piece from assorted spices commonly found in the home, but of course those ultimately organic in origin.

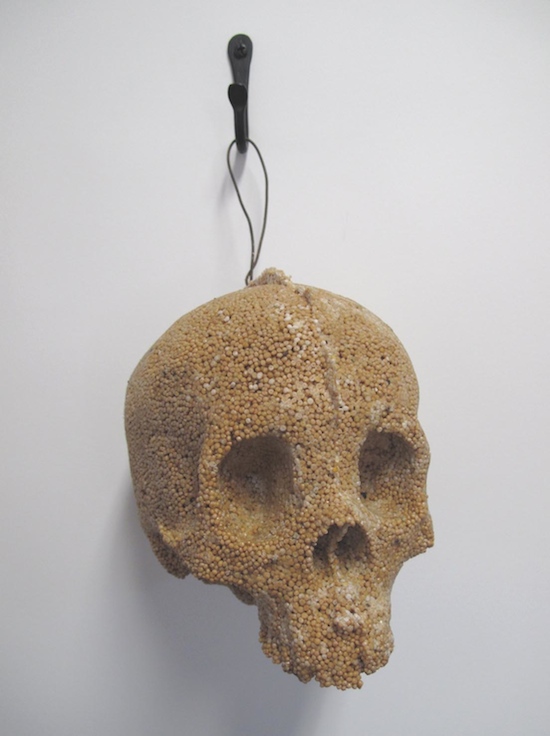

Annatto Seed Skull

In each case, the seeds, kernels, leaves or other dried plant matter are glued together then sculpted into human form before being hooked up in decorative style, where they gaze out at the observer like cookery’s answer to the trophies of some headhunting tribe. Still, any more lurid pop culture references seem allayed by the earthy colors and rough grains of the pieces.

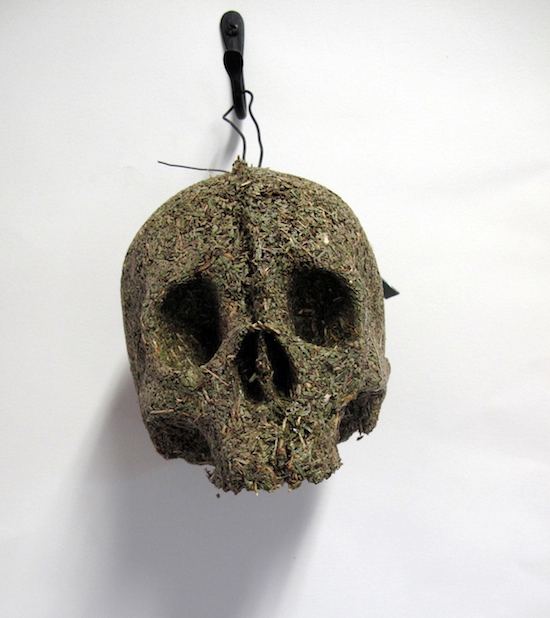

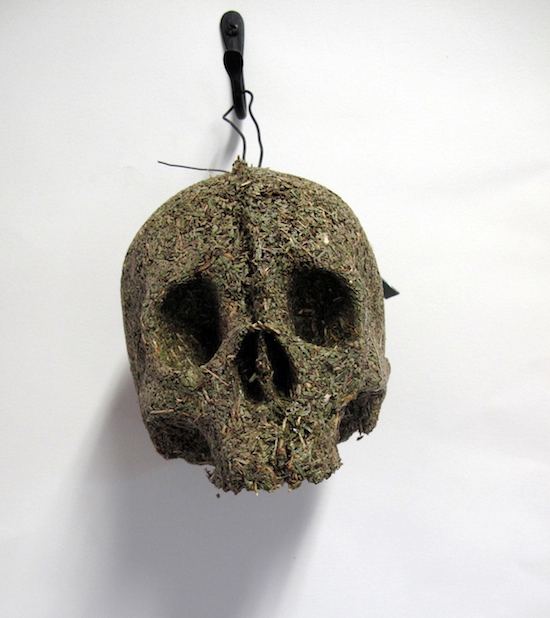

Coconut Skull

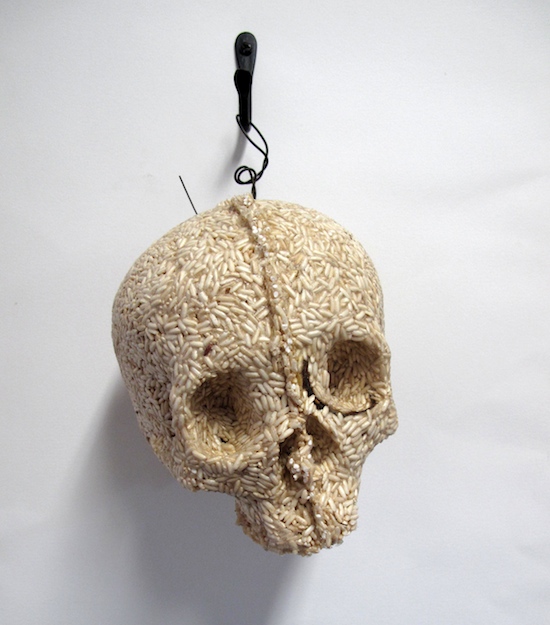

Dozens of different herbs, spices, seasonings and other household staples were used — from rose, lavender, millet seed and juniper berries, to red chili, glutinous rice and yellow split mung beans. In 2010, Altman’s work was shown in “Dead or Alive,” an exhibition held at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, which “showcase[d] the work of over 30 international artists who transform organic materials and objects that were once produced by or part of living organisms.” According to the

Financial Times: “Helen Altman mixed cumin, paprika and other fragrant flavorings with gelatin, and shaped the paste into 60 life-size human skulls, arranged into a wall-sized grid.”

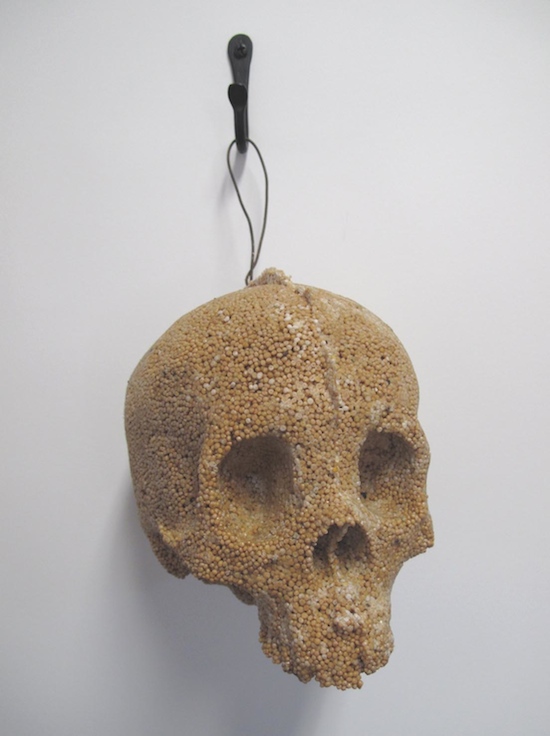

Balsam Fir Skull

It’s fitting that Altman’s work was presented in a show with such morbid yet life-affirming concerns — themes that lie at the heart of what both art and recycling are about. Art creates by drawing on the fabric of life and other artistic offerings; recycling does the same with physical materials, whether produced by man or by nature. By apparently combining both ideas in her work, Altman brings this cycle of death and rebirth into relief. Or seems to.

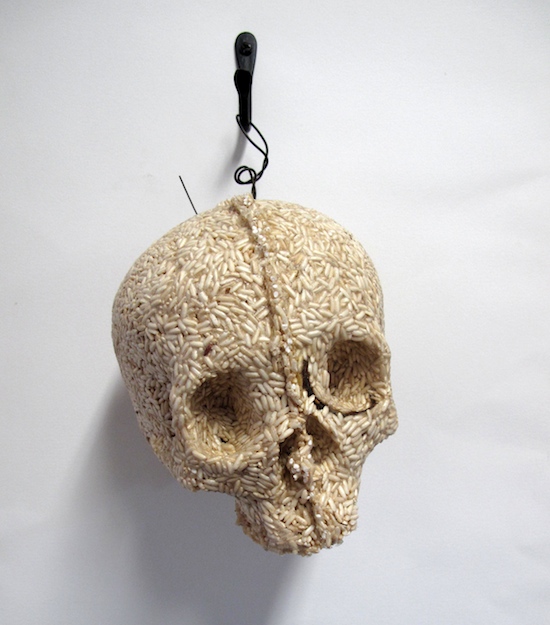

Mustard Seed Skull

As the artist told us, the different media she uses aren’t recycled, strictly speaking: “I buy all sorts of different materials for use in the skulls based on color, fragrance and other criteria,” says Altman. “The skulls are solid. For instance, if the media is ‘poppy seed’ the skull is solid poppy seed. I use a 16-gauge wire within the mixture to hang the skulls from. Most of my art has used commonplace and everyday materials and objects. I feel a special love for the things which are familiar.” Repurposing, then, if not quite recycling in action; but given the materials the skulls are made of, they certainly hold the potential to be reclaimed by the natural world.

Chinese Tea Skull

“I only use materials that are safe around my home,” says Altman. “The best thing about the skulls is that they are ‘all natural’ and safe for wildlife to eat. That is how the series started. I used birdseed to make feeders for the birds. You can buy those bell-shaped pressed-seed feeders at almost every feed and pet store. A skull shape made as much sense (more sense to me) as a ‘bell’ did and I used all sorts of seeds that could be eaten by birds and other wildlife. I mix and pack the skulls on a table in my back yard and there is usually leftover material. If the media is something the birds like, I’ll put it on a feeder for them. Sometimes the media actually sprouts under the table. The homemade ‘glue’ (my own secret recipe) is also edible.”

Split Yellow Mung Bean Skull

The pieces also evoke other associations: when smelling the co-mingled spices, does the diversity of olfactory sensations somehow mirror our differences when we are alive — even as the starkly grinning skulls remind us of the ultimate sameness that awaits us in death? Food for thought.

Skulls (side view)

At any rate, the concept of reuse is an ingredient in Altman’s work. In her artist’s statement, she says: “Many of my works use commonplace materials and objects. I respond to ready-made objects that are often discards or flawed in some obvious way. Alterations in these familiar things elevate them and draw parallels to our own human predicament.”

Clove Skull

This ability of art to turn the everyday into the extraordinary, and to edify while doing so, is one of the things that makes it special. If you were to hang these skulls as ornaments around the house, while they sure might come in handy if your jar of herbs and spices ran dry, hell, they might even make you think a little, too.

Ginger Root Skull

Ordinary found materials — like these ones, identified with cooking and food — also serve another thematic purpose in Altman’s artistic output. She is concerned, as New York’s DCKT Contemporary gallery highlights, with “notions of reality versus artificiality in everyday life.” “I am also interested in mimics and replicas,” explains the artist. “It is a happy moment for me when I can create objects that are simultaneously convincing and yet blatantly absurd in their obvious artificiality.”

Citrus Peel Skull

At a distance, these skulls may indeed look authentic, like the real thing, but move closer and their odor takes over, and we realize they are merely reproductions of an often, indeed endlessly repeated cultural image.

Glutinous Rice Skull

As Flavor Wire points out: “While you can spot them in the celebrated work of famous visual artists like Dali, Picasso and Mapplethorpe, the use of skulls in the design world is admittedly more divisive. For some, they are a symbol that brings to mind pirate ships or poisonous substances; for others, tacky biker tattoos and trucker hats.”

Through the ages, whether in high culture or low, skulls have been the ultimate symbol of death, mocking us with their blank expressions or their leering stares. Altman’s mock skulls are a welcome guest at the party — spicy reminders that while art may strive to imitate life, death is something unknowable and beyond imitation.

Rose Skull

Or maybe, when it comes to our ideas about mortality, Oscar Wilde was right when he said, “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” Perhaps the way we think about meeting our maker, or facing the Grim Reaper, is only made possible by artistic invention.

Bay Leaf Skull

While a fascination with death may be nothing new for the visual arts, like the sudden blast of a pungent perfume, Altman’s Spice Skulls are art objects that draw attention to the endless recycling of culture and nature, life and death, more beautifully than most. In the very make-up of many of these sculptures, which look at the nature of skulls, we see the fine grains of seeds that would have once borne life — and could still feed it.

Calendula Skull

Born in Tuscaloosa, AL, Altman graduated with a B.F.A. from the University of Alabama in 1981, later achieving her M.A. from the same school in 1986, and an M.F.A. from the University of North Texas in 1989. Her wide-ranging work is displayed in permanent collections in Texas (Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont; Dallas Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston), California (Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego) and Alabama (Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa), and has been exhibited in various galleries across the country. She currently lives in Fort Worth, TX, with her four dogs.

Special thanks to Helen Altman for taking the time to talk to us and for permission to use her images.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5