All images courtesy of Rob Pettit.

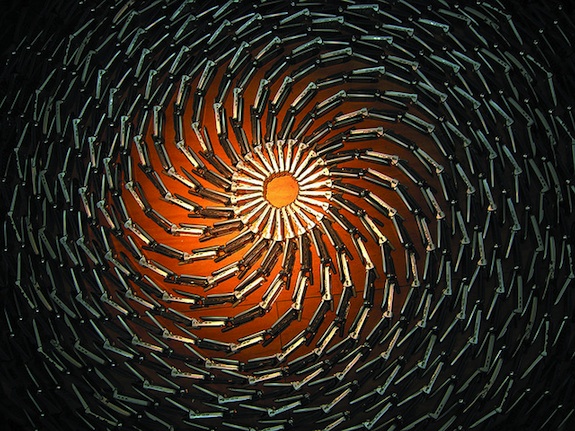

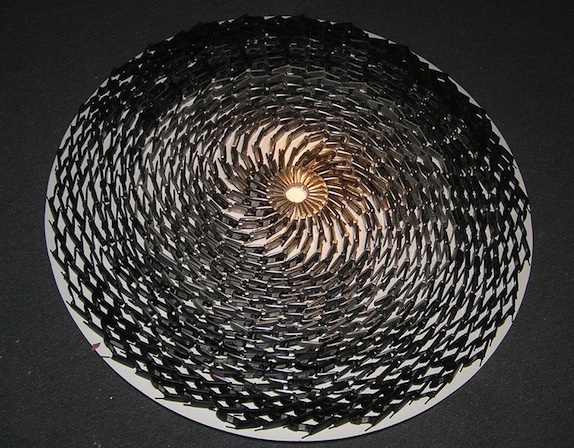

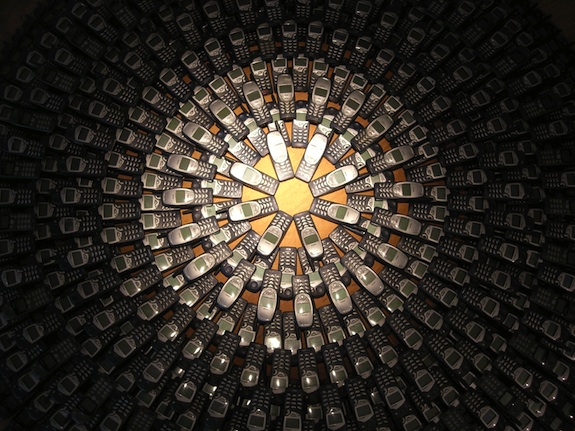

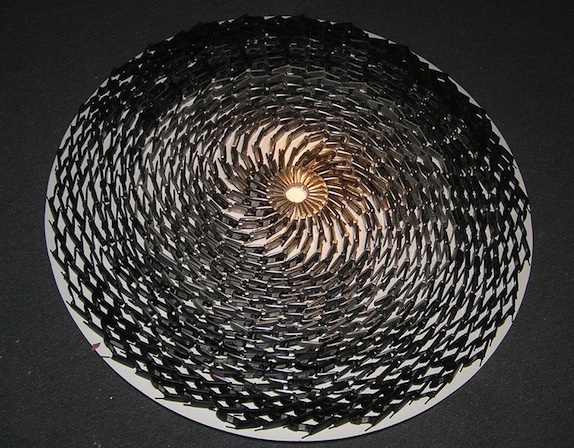

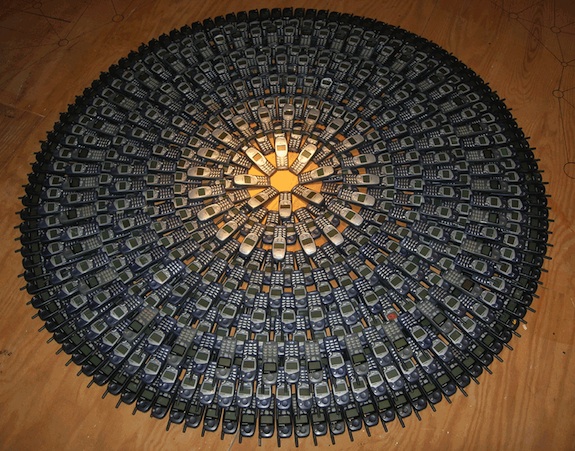

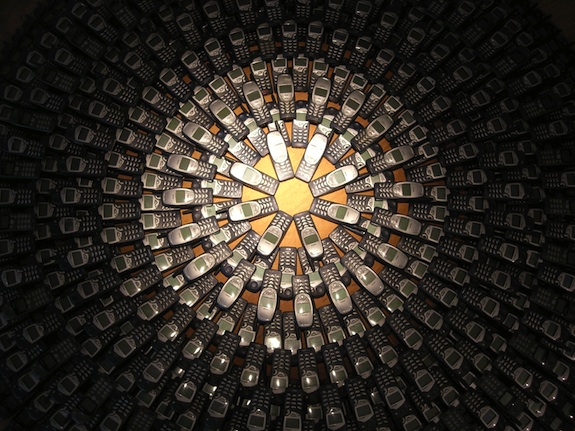

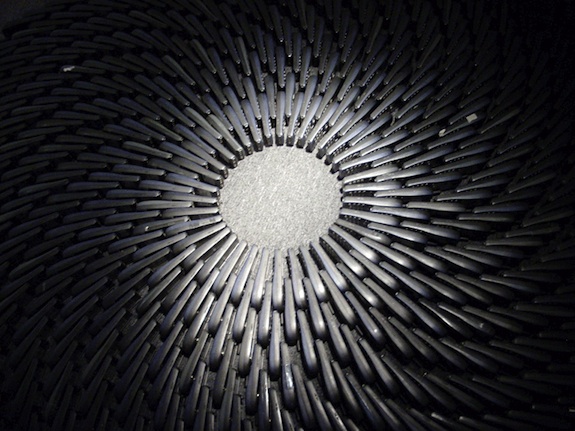

Zone out while looking down at these immense artworks and you might feel as though you’re looking into the eye of a galaxy, or the center of a vortex. It’s easy to be mesmerized when staring into the endless whirls and volutions of spirals — one of nature’s most significant shapes — and it’s no different here. Yet, while we’re familiar with seeing cyclones made of air molecules or the helices of DNA, spirals made of thousands of discarded cell phones… well now that’s something different. These are the sculptures of Rob Pettit, an artist whose work it would be safe to say is a calling.

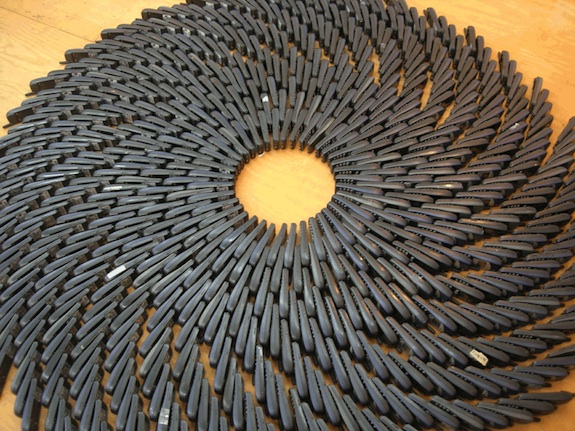

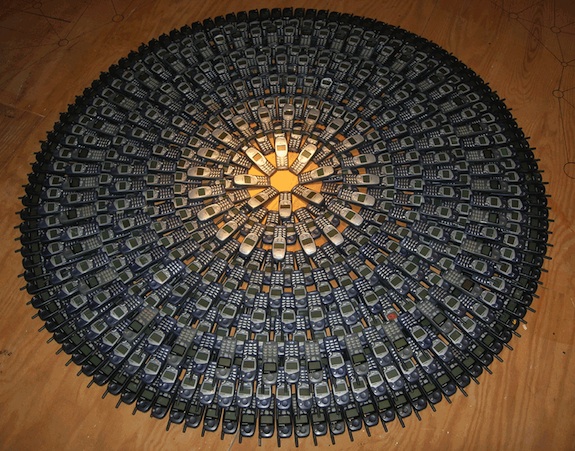

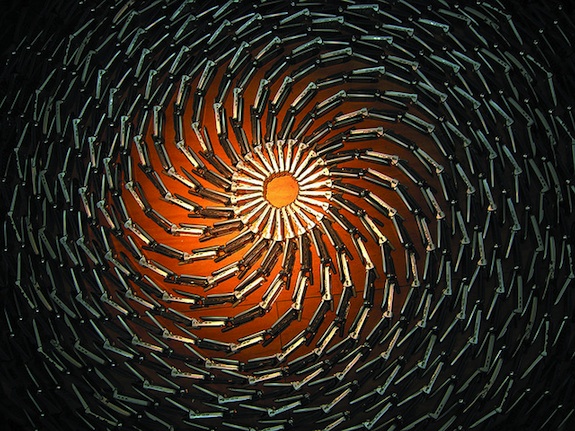

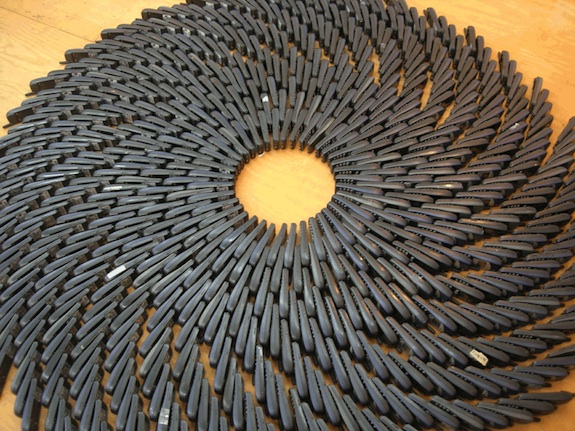

Pettit’s art installations have been created by arranging old cell phones into giant shapes, as geometrically perfect as they are spellbinding. Pettit says: “I have collected over 5,000 mobile phones and made work from them in various mediums: several large floor sculptures, light pieces, sound and drawings made up from over 40,000 tiny ink hand-drawn cell phones.” All are interesting, but it’s the coiled simplicity of the spirals that capture the imagination — not least because they’re all recycled and reused, saved from becoming landfill by a higher purpose — as an artistic medium.

Whether dropped and broken, drowned in toilets or baths, or having given up the ghost due to more natural causes, every day, more and more cell phones die, their screens fading to black for the final time. No funeral ceremony awaits these faithful servants; once they’re outdated, they’re scrapped one way or another, ready to be replaced by the latest models. By forming so many of these everyday objects into spirals — potentially infinite curves emanating from a central point — Pettit aims to “highlight the proliferation and waste of cell phones.” A single invention spawned a multitude of flip-top clones.

Used by one and all in our rapidly developing technological age, and containing materials that are poisonous if allowed to enter ecosystems, it’s no wonder the mass of discarded mobile phones have become a significant tributary into America’s waste stream. Despite an awareness that the problem of electronic waste is real and pressing, it’s slightly alarming to know that “7% of mobile phone owners still throw away their old phones,” and from there it’s just a small step to the toxic chemicals they contain seeping into the groundwater system where they can cause untold harm to plant and animal life.

So, how can these oddly omnipresent handheld devices be safely disposed of to prevent them from becoming so dangerous in death? The easy solution is the electronic-recycling industry: computer components like circuit boards contain valuable elements and substances well worth salvaging, including metals such as copper and gold. Green art is another option; but if you’re keen to work with a large canvas you’re going to need to collect thousands of the obsolete handsets — and of course, Pettit already beat you to the punch. So, we were interested to know, where did Pettit retrieve all these phones from?

Well, if you want to lay your hands on piles of thrown-away objects almost everyone possesses, you start locally, asking anyone you can, and recycling companies in particular provided a big part of the answer. As Pettit told

The Brooklyn Ink: “I was always losing my phone, and the idea came out of that. I wanted something free, and people have cell phones lying around. I started asking around, and 10 became 20 became 100 became 1,000 became 5,000. There’s 3,000 in this studio, and another 2,000 at my dad’s place in Albany. Moving them is a pain. I used big shovels, snow shovels, to get them into boxes.”

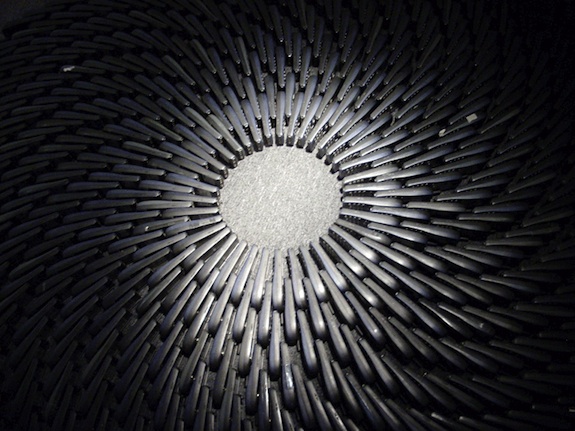

More than 5,000 outdated cell phones is a lot to own, and storing and transporting them may be a pain, but it’s obviously worth it for Pettit, who has been creating his installations since 2008. “It’s meditation, setting them up,” he says. “Kind of like Buddhist monks making their sand designs and then dumping them in the river.” Circular designs and more random heaps also form part of his repertoire, but each mass grave commands attention — whether lying in the middle of the room or fanning out on all directions on walls. There are some real dinosaurs in there, too — some from as far back as the early ’80s.

Pettit doesn’t stop at sculptures, either. He has created drawings of different descriptions: strange landscapes with towers, people using phones, cell phone grids and binary codes — all of them made of myriad cell phones, and all of them turning our minds on to think about our relationships with this technology — and how it affects our relationship with each other. By making mobile phones both the central motif and medium for his art, he not only reminds us how many of our little friends are produced only to become useless and forsaken; he shows how they have shaped the very world we live in.

Beautiful as they are, these installations call attention to the high-speed, ever more globalized, consumer-driven culture in which we are all immersed — always moving yet in touch, interconnected by telecommunications whether we like it or not. Is this situation one of freedom, or, like a vortex, is it a trap? Especially with the advent of smartphones — the mobile computers of the future — are we doomed to be sucked into a maelstrom that somehow has the character of a network? Forgive the melodrama, but wouldn’t you be lost without your cell phone? Such ideas are not lost on Pettit.

“We’ve become a technology-dependent generation,” says the artist. “Take a look at communication, for example. What used to be simple smoke signals used by our cavemen ancestors have grown to alphabets, letters, telegraphs and now telecommunication. Mobile phones used to be a fad, now it has become a commodity. With human culture leaning more toward globalization and a fast-paced lifestyle, mobile phones will become a more prominent part of our existence. One only has to take a look at the steady influx of latest mobile phones to see how much this trend has developed through the years.”

And it’s a trend that doesn’t look like dying any time soon. Has Pettit successfully delivered the message he hoped to send? We reckon so. A carpenter by trade, Pettit studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and now lives in Brooklyn, where he creates his work out of his studio. To see more of his work, visit his

website here.

Thanks to the artist for permission to use his wonderful images.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6