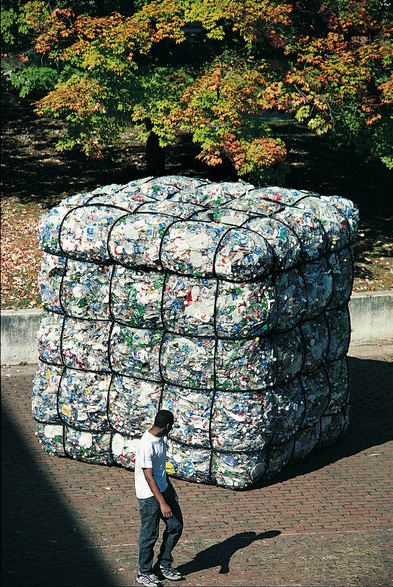

“Freight and Barrel,” 2004, Three Rivers Arts Festival, Pittsburgh, crushed plastics. All images courtesy of Steven Siegel.

Before you start licking your lips at the thought of tucking into a giant burrito, you might want to consider what the delicacy before you contains. If this is junk food, then it’s never been super-sized like this before — and it’s never contained more junk. But let’s get serious for a second. Like others of its kind dotted around the globe, this giant form, located in Pittsburgh, looms, like a monolith — something that might almost have been made by natural forces but which bears the unmistakable hallmarks of the human touch.

“Two of ’em,” 2009, Penn State Berks, Reading, PA — bamboo, aluminum cans

In truth, this is junk art on a massive scale, each sculpture created out of the discarded detritus of modern life yet somehow existing in a certain harmony with its surroundings. The pieces are the brainchild and handiwork of New York-born land artist Steven Siegel. Is there some deep-rooted ecological message contained within these strange pod-shaped and boulder-like forms? Undoubtedly. But Siegel isn’t going to bash you over the head with a hammer about it. He’s too busy using such tools to craft his monumental masterpieces.

“Bale,” 2001, University of Virginia, Charlottesville — crushed plastic

In an article in the journal Wild Apples, Siegel speaks of his work as “art that engages the natural environment and the specifics of a particular place,” and you soon see what he means. Despite the materials they are made of, Siegel’s sculptures are built into but also transform their environment; there seems to be a symbiotic relationship between the two. The artworks make us aware of the waste materials out of which they are composed yet stand as all but organic landmarks in themselves — making us question what is natural and what is not.

“It Goes Under,” 2008, University of Wyoming Museum of Art, Laramie — wood mulch, window screen

In an interview with Sculpture magazine, Siegel said: “I don’t really believe in the word ‘natural,’ because I believe that we are the physical landscape, not only by our physical presence, but also by the messes we leave and the way we reconfigure all of the material around us — from the roadway to the recycling of cans to nuclear waste.” His sculptures, man made but inspired by nature’s aesthetics, are cases in point. Waste returns from whence it came, blurring the boundaries between man and nature. Still thinking about that big old burrito?

“It Goes Under,” 2008, University of Wyoming Museum of Art, Laramie

Siegel has used trash and scrap of all descriptions in his art — from compressed soda cans, empty drinks cartons and crushed plastic bottles, to shredded tires and old floppy and compact disks. In many of his pieces, these materials are bundled and compacted into minimalist forms — cubes, barrels and bails bound up with netting and hose. What unites these abstract pieces? For Siegel, the answer is deceptively simple: “Life is about containers. Starting with the atom, the molecule, the cell, a tree, even humans — all these elements are containers.”

“Beach Blocks,” 2009, Sirolo, Italy, commissioned by AliveShoes

Siegel continues: “This means that you can stand up and function, from your DNA right up to your eyeballs. It is all incredibly complex.” If these artworks are metaphors for biological life, then how they evolve in their settings brings this home. Exposed to the elements, nature takes its course, reclaims her own: Insects take residence in their nooks and crannies, and depending on the materials, molds and fungi grow, saplings sprout, carpets of moss appear. These sculptures have a lifespan of their own and, eventually, will be broken down to nothing.

“Beach Blocks,” 2009, Sirolo, Italy

Where’s the recycling in all of this? Like a half-eaten jumbo burrito you just can’t get through, it’s staring you in the face — and not simply in the various materials Siegel uses, be it e-waste, aluminum, glass or plastic. As the artist has said: “Everything on the earth is recycled. That is a given. Recycling just is. Rocks, buildings, people — everything. People say I am an environmental artist because I use recycled materials. Good for me. I care about the environment. But that is an easy, lightweight explanation. It doesn’t require much thought.”

“Can Can,” 2002, Bowling Green State University, Ohio — crushed aluminum cans

Of course, there’s a lot to be said for finding new life for pre-consumer and recycled waste, as Siegel does in his art, but reuse and sustainability are only part of the story. Siegel’s statement is more than a collective slap on the wrist about issues such as the waste stream, our plunder of the planet’s natural resources and the darned mess we’re making. It’s a bigger vision of how we as a species and individual organisms interact with the environment — like the sculptures both impacting on and influenced by our natural surroundings.

“Grass, Paper, Glass,” 2006, Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ

When we contacted him, Siegel offered us a glimpse of where he’s coming from: “Even though I consider myself an environmentalist, and I am a very political person, and to many my work expresses a political environmentalist’s concerns, I do not make art for political reasons. I am interested primarily in aesthetics, and would not be an artist for any other reason.” And yet, by using our day-to-day waste and the debris industry creates through overproduction and overruns, Siegel is making a difference, however infinitesimal.

“Valerio’s Hidden Gem,” 2009, Arte Sella, Italy — Tetra Pak packages

“Typically, when I work on a site, the first thing I ask about is the type of materials that might be available in large quantities,” Siegel has said of the many pieces he has built in universities, museums, sculpture parks and private venues across the U.S., Europe and Asia. Then he gets help from staff, volunteer students and paid assistants, all learning the craft of making such large-scale sculptures. More hands make lighter work of the digging, loading, piling, sawing, clipping and cutting it takes to make the colossal pieces.

“Scale,” 2002, Abington Art Center, Jenkintown, PA — paper

Popular among these are Siegel’s impressive multilayered newspaper accumulations — reimagined ridges in landscapes, natural bridges over gullies and giant rock formations, some a haven to plant life. One of them, “Scale,” stood 22 feet tall before it collapsed and crumbled into the earth. These stacks of paper are altered more dramatically by natural processes than some of the other sculptures, but address similar themes about our place on the planet and “the essential cycles of deposit and decay that underlie the making of the land.”

“Like a rock, from a tree?” 2008, Geumgang Nature Art Biennale, Gongju, Korea — paper

These landmarks are part of the artist’s concern with geology, which was born out of an interest in “how we reintroduce materials back into the landscape, specifically landfills.” Landfills, as Siegel notes, have become a new kind of human geology; indeed the artist’s first newspaper structures were made on New York’s Staten Island — until recently home to the world’s largest rubbish dump. Humans add as much to the ongoing accumulation of the earth’s strata as anything; the difference is, our contribution largely constitutes junk.

“Big, With Rift,” 2009, DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA

Siegel has been creating his amazing sculptural installations in different locations around the world since the late ’70s — always calling attention to our fleeting position in time as specks in the grand scheme of things. Before embarking on his career, he graduated with a B.A. from Hampshire College in Massachusetts (1976) and gained a Masters of Fine Arts from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn (1978). He currently lives in Hudson River Valley, NY.

“Bridge 2,” 2009, Arte Sella, Italy — paper

Special thanks to Steven Siegel for permission to use these images of his work. Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5