Thriving both intellectually and socially in a school system is entirely possible, but sometimes the daily grind can get the best of even the most studious eager beaver. Navigating the slings and arrows hurled by fellow students who, for whatever reason, favor spitballs and ill-conceived nicknames over the actual absorption of knowledge can be just as energy intensive as shuffling through drafty old hallways or walking by water fountains that continue to flow even when no one is sipping.

In spite of the many valuable things that learning institutions offer today’s students, there is one common denominator tying the majority of them together — a voluminous carbon cloud lingering right above the roof. Let’s just call it like it is. School buildings across the country, and even the world, are so outdated in terms of their construction materials and energy delivery systems that they might as well convert their football fields into coal mines and — just for kicks — add hydrofracking to the mix.

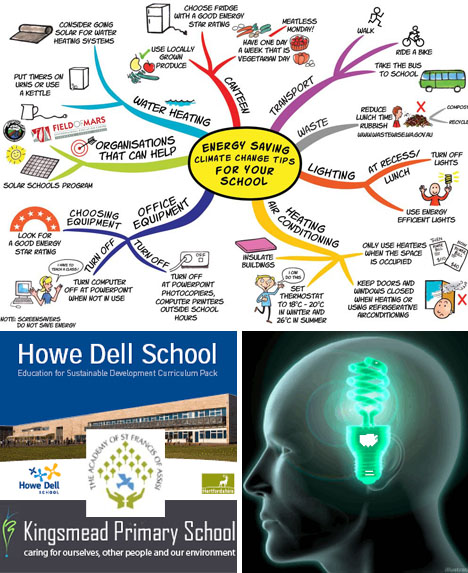

OK, perhaps that’s a bit dramatic, but in all honesty, schools are energy vampires. They operate at an exceedingly high level of inefficiency because in many cases, they were constructed decades before we had a clue about things like LEED certification and Energy Star-rated windows. Britain’s former prime minister Tony Blair recognized the value of investing in his country’s school system (via Building Schools for the Future) in order to create a greener tomorrow with a multibillion-dollar plan. Bring old schools into the 21st century with strategic updates, including imaginative design features, proper ventilation, the maximization of natural daylight and the utilization of sustainable construction materials. While the cutting-edge initiative has since been tabled with funds channeled toward other projects deemed more practical, the following three schools were fortunate enough (along with about 500 others) to reap the benefits of a new eco-facelift while the greening was in full swing: Kingsmead Primary School in Cheshire, England- Locally sourced natural timber exterior

- Biomass boiler heats school

- A rooftop rainwater collection trough feeds toilets via clear pipes so that children can witness the eco-spectacle.

- Windows automatically close when it’s raining outside, blinds close when the sun is shining brightly.

- Parents are encouraged to walk or bike children to school in keeping with the overall green theme.

- Awarded a BREEAM excellent rating for its sustainable features

- Concrete building achieves high thermal mass.

- Features transparent ethylene tetrafluoroethylene roofs studded with sedum plants and/or recycled crushed local seashells

- Photovoltaic panels heat water and generate electricity

- Strategic use of natural daylight and cross ventilation

- Rainwater harvesting tanks store 5,000 liters for toilet flushing and solar water heating.

- Students are responsible for planting/maintaining gardens and making sure that recyclable materials are collected throughout the grounds.

- Eco-inspired learning curriculum

- Super-insulated

- Toilets use recycled rainwater.

- Kitchen/bathroom sink water is heated via solar heating panels.

- Photovoltaic panels generate supplemental electricity.

- Sedum plants cover the roofs.

- Skylights significantly reduce electric bills.

- Recycled drainpipe desks, recycled yogurt cup plastic sink countertops/splash guards

- Easily replaceable carpet squares cover the floor, reducing waste.

- Features the world’s first underground heating system (Interseasonal Heat Transfer) beneath the playground. It harnesses solar heat generated from the tarmac playground into water, which is then pumped though underground pipes and stored in thermal banks for later use, reducing carbon emissions by 50% compared to conventional school boilers.

- On-site wind turbine!