Consuming a refreshing beverage requires very little mental exertion. Simply scan the countless brands and flavors available at your local store, purchase a variety that sounds appealing, open it up and finally glug-glug-glug. Ah, how sweet it is…

Are you kidding? Things aren’t nearly as cut and dry anymore.

These days, in addition to having access to seemingly countless types of thirst quenchers, we also have the option of selecting organically produced versions and some that are even packaged in BPA-free containers (which is ideal for those eager to limit their exposure to hormone-altering chemicals). Decisions, decisions.

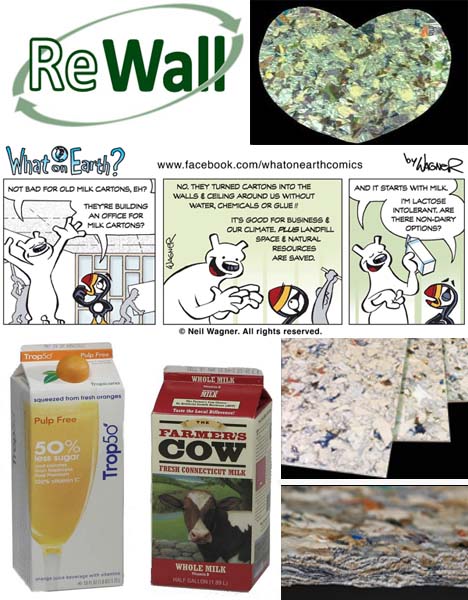

Let’s say you favor milk and juice. If you typically purchase both items in half-gallon quantities, you will most likely end up placing gable-top, polyethylene-coated paper cartons in your shopping cart. Upon polishing them off, you’ll then rinse out the containers (they’re paper, after all!) before slam-dunking them in your household recycling collection bin.

Um, apparently that’s not what happens at all. According to the EPA’s municipal waste stream statistics for 2008, at least in the case of milk cartons, 490,000 tons were produced, but a mere 0.05% of them (the equivalent of just 5,000 tons) were actually recycled.

That seems rather odd, doesn’t it? Given the fact that they are made with totally recyclable paper, and many major milk brands even emblazon the words “Please Recycle!” on the side of the container, clearly there must be a missing link. Bingo.

- Very few municipalities have established processing centers devoted solely to recycling poly-coated paper beverage containers.

- Minimal recycling volume results in negligible profit for municipalities, which makes the whole process rather unappealing.

- Consumers rarely take the time to wash containers out, causing residual milk to go bad. The bacterial and mold residues then compromise the integrity of the containers, prompting them to partially decompose.