All images used with permission of Beto Janz.

From the early days of the Bones Brigade skateboarding team, with their classic Ripper insignia, to the minimal black and white design of the Zero skateboard company of the ’90s, skulls have always been synonymous with skateboarding art.

Maybe it’s because whether carving along the sidewalk swell of the concrete sprawl or dropping in on the vertical faces of unforgiving, drained swimming pools, skaters are that little bit closer to danger — and possibly death — than your middle-of-the-road, law-abiding citizen. Maybe it’s just the fact that skulls look gnarly. Whatever. Skating prides itself on being hardcore to the bone.

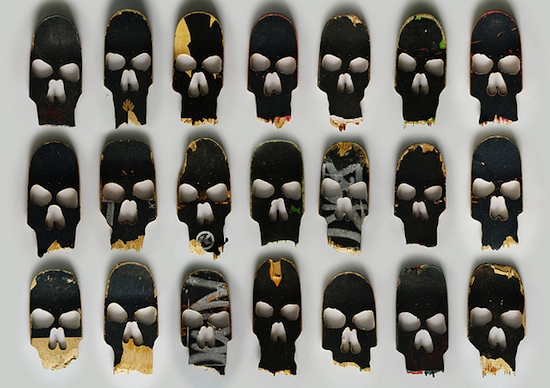

In the bone-crunching world of street skating — where slams regularly cost ankles — a skateboard isn’t going to last forever. In fact, if you’re ollying steps or grinding rails all day, you’ll be lucky if your board lasts you a month. Don’t take our word for it, though; talk to Brazilian graphic designer and skater Beto Janz, who found he had all the materials he needed in the form of snapped decks to create his own take on the whole skeletal aesthetic: a series of stylistically simple yet striking skulls, grinning at the observer like the ’90s never ended.

The project rose from the crypt of a marketing campaign — albeit one on a small, DIY scale — to celebrate the new structure of a skate store called Ultra Séries. “In order to promote this new spot,” we’re told, “designer Beto Janz customized used and broken decks, using the decks to produce skulls. Stickers with the brand and the address of the new stores were applied to them and they were left on streets nearby main skateboard places around Curitiba, Brazil. Therefore, anyone who finds them gets them. An ‘underground’ way of promoting the store.”

Underground, it’s true, but then skateboarding has a long tradition of resistance to the mainstream. What struck us as different here was the strong recycling current that runs through the story. Most of it is obvious: used and useless boards, rather than finding their way into the garbage dump or even onto the wood-recycling pile, are reincarnated to serve a cultural purpose, if not quite a practical one. What’s more, they’re put in places where they can be retrieved by the kids that, presumably, they came from. Like wheels spinning around ball bearings, the cycle goes on.

Whether on the streets in the pieces of graffiti writers, or in galleries exhibiting the work of top artists like Damien Hirst and

Subodh Gupta, skulls are ever-present in our culture, endlessly recycled just as they are in nature — ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The cycle of life, and art, continues.

Here, the teeth are formed out of the splintered plywood of the boards, while eye and nose sockets and the line of the jaw have been sawn out to complete the effect. Simple, effective, easy to be pinned to a fence or slid beneath a skate ramp, where some young skater can find them.

We picked Janz’s brains about the recycling aspect of his project, giving something back to the kids, and skateboarding’s history of using skulls in its art.

Where did he salvage the used and broken boards from? “From the skate shop, Ultra Séries. The customers left the old broken decks there when they bought new ones, so, I got them,” he tells 1-800-RECYCLING. “I always wanted to use broken decks for something, because they are very good pieces of wood and it’s very meaningful for those who skate. I think that broken decks have an art concept; they’re not trash.”

Skateboard designs themselves led the way in the art the subculture conceived for itself, with guys like Jim Philips and Vernon Johnson carving a groove that others followed. But why skulls and skating? What was Janz’s take on the kinship? “Skateboarding involves some risks and dangers, bruises, broken bones and even death,” he says. “One of the reasons for the relationship between skulls and skateboarding is, I believe, precisely this: to demonstrate the lack of fear about the risks we are being exposed to, demonstrated in practice with the feet on the skateboard.”

“Another reason is skateboarding is not a sport; it involves music, fashion and attitude. It’s more complex than a simple sport. Besides all of that, it was born and grew up in a parallel world, an underground world. Today, it’s been turned into a moneymaker and marketing factory, but it still has ties with its roots. At the beginning, those who were from the underground world wanted to shock society, and one way for them to do that was through the use of skulls, to show their disdain for death, for example — a device to shock, to demonstrate how bad they were.”

And now? “I think today, it no longer makes much sense,” reckons the designer. Still, you are where you come from – and skateboarding is the Brazilian designer’s world. “I live in this culture, I’ve heard the kinds of music from the beginning of punk and skateboarding; I watch horror movies. This is my universe, and for this reason, I feel good about making something that represents me as well.” Of course, the element of recycling isn’t lost on him either. “And there is a paradox in bringing something that was disposable back to life in a skull shape,” he adds.

Reflecting on his series of skulls and how they were left to be recovered by those who would appreciate them, Janz wraps things up: “One of the things that I liked most in the project is that it didn’t cost a penny, it had no relation to money. Lots of people think this is stupid, but for me, it’s important. The skulls were thrown in the streets, near skate parks, for whoever finds and wants to have them. They have a sticker, informing you that you’ve won a T-shirt if you take the skull to the store, which spreads word about the store. And obviously, you won the skull as well.”

Good enough for us. So, any last thoughts? “A special thanks to the cop who took one of the decks for himself,” says Janz.

Special thanks to Beto Janz for permission to use his images and for taking the time to answer our questions. You can visit his website here.